Dystopia and the mainstreaming of anti-Asian racism, part 1

The origins of anti-immigration extremism in dystopian fiction

Editor’s note, 5/26/2023: I changed the headline to make it more descriptive.

The end of the Civil War, and the “peculiar institution” that precipitated it, ushered in a fresh generation of White racial anxieties, evolved but not disconnected from those that preceded it. In the wake of the Civil War, dystopian writers found new audiences by framing racial fears in the potential for another apocalyptic, nation-breaking conflict. But the range of complexions for the enemy within shifted, as the trembling gaze of White America turned from the South to the Far East.

A wave of Chinese emigration began in the mid-1800s, driven by economic conditions at home and surging demand for cheap labor to fill the vacuum created by the abolition of slavery first in the British Empire and then in the United States. Chinese immigrants traveled to the United States to make new lives for themselves, first filling a need for workers that had resulted from the California Gold Rush, then filling low-paid agricultural and factory jobs, perhaps most significantly providing the back-breaking toil required to build a transcontinental railroad.

Like many immigrants before and since, Chinese people soon became the target of opportunistic fear and hatred, in Europe, Australia and especially the United States, where White racial fragility was heavily filtered through Civil War trauma.

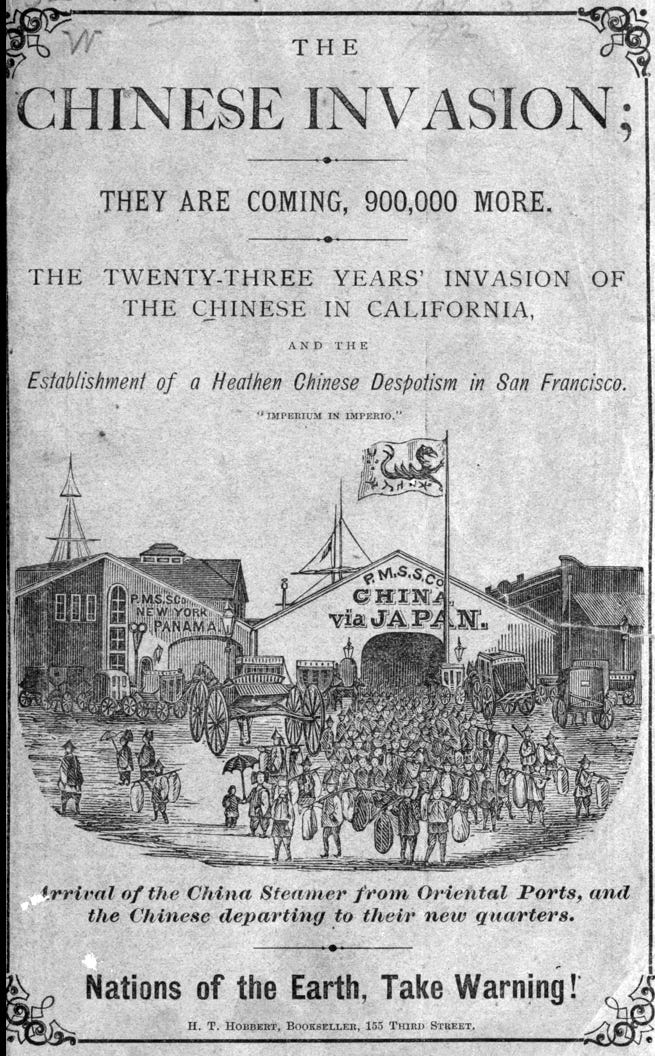

“The African now enjoys the privileges of an American citizen, but it was only after a revolution of unparalleled magnitude that he reached such a condition,” wrote one H.J. West, in an edited volume of news stories and essays “ripped from the headlines” under the weighty title Chinese invasion : they are coming, 900,000 more : the twenty-three years' invasion of the Chinese in California, and the establishment of a heathen Chinese despotism in San Francisco. “No enlightened Patriot would wish to see the day or the perfection of a system that would involve the nation in another rebellion, sweeping across the continent like a tornado.”

Invasion rhetoric and comparisons to the catastrophe of the Civil War quickly came to dominate the immigration debate, in race-baiting books and newspaper articles all over the United States, as well as in Britain and Australia. An 1877 brief under the heading “The Chinese Invasion” in the Kansas Herald warned “There is no end to the supply of Chinamen, and if our laws permit them to come, they will come by millions and entirely change the character of our country and our institutions.”[i]

The newspapers contained hundreds, perhaps thousands, of similar examples. Criticizing Republican opponents of an immigration crackdown in a front-page editorial in the San Francisco Examiner, journalist Frank M. Pixley wrote, “It is to them a conflict over an idea. To us, it is the invasion of a horde of people, which, if unrestricted, will destroy San Francisco. … This is not used as a metaphor.”[ii]

Nor did the literary defenders of White supremacy take it as metaphor, unleashing a remarkable, decades-long run of racist dystopian novels with titles such as Under the Flag of the Cross (1908), and A Short and Truthful History of the Taking of California and Oregon by the Chinese in the Year 1899 (1882). Many of these blistering tracts portrayed Chinese immigrants as a fifth column that would inevitably be weaponized to destroy American culture and values, while others depicted a global race war unmoored from the immigration issue. The surging popularity of the dystopian fiction format, now fully mature as a literary genre, fueled the fires of anti-immigration movements.

Atwell Whitney’s sole claim to fame is authorship of what appears to be the first full-length novel of the “yellow peril” genre. Almond-Eyed: The Great Agitator or A Story of the Day, follows the format of the frontier romance, but reverses the privilege. Instead of portraying a “heroic” White invasion of native American territory, the 1878 novel placed White America on defense against rapacious Chinese immigrants. The book’s title was an ethnic slur commonly used to describe Asians in 19th century media.

The story goes: In the American hamlet of Yarbtown, the immigrants are welcomed by avaricious business leaders seeking cheap labor and naïve Christians seeking opportunities to evangelize. The protagonist lovers, Job and Bessie, are among the few to recognize the threat. Yarbtown is soon overwhelmed by Chinese-run vice dens, including gambling and opium, which corrupt morals of the White citizenry, and eventually result in a deadly outbreak of smallpox.

While Job and Bessie manage to eke out a happy ending for themselves, Yarbtown is not so lucky, sinking into irretrievable degradation and despair thanks to the inaction of Whites who thought that the Chinese could be profitably integrated into American life. “The stream of heathen men and women still comes pouring in, filling the places which should be occupied by the Caucasian race,” Whitney concludes. “… Good people, what shall be done?”

Almond-Eyed came and went with little fanfare, but it was the vanguard of what would be a wildly popular genre of anti-Asian dystopia—a corpus comprised of at least 23 works of fiction, including books and short stories—published in the 50 years between 1878 and 1918, with still more arriving later in the 20th century. The language and themes of these early works would reverberate through the dystopian genre for well over 100 years, haunting us still today.

One of the best-known pioneers of the format was Last Days of the Republic (1880), by Pierton W. Dooner, describing a near-future disaster that the author defended as mathematical certainty. Like some of its antebellum predecessors, the book is barely a novel, presenting a dry summary of anticipated future political developments that naturally lead to disaster. Partisan divisions in post-Civil War America obstruct efforts to restrict Chinese immigration, and profiteers urge looser laws in order to build a cheaper work force. By the time the Chinese Empire formally invades, naturalized Chinese immigrants have already seized many levers of political power simply by winning elections. Black people are strangely erased from the narrative; according to the author they had “disappeared” from the post-Civil War social landscape, perhaps (it is suggested) having returned to Africa.

Awakening to its danger too late, the White population attempts insurrection “in favor of State Sovereignty and White supremacy,” led by Southern stalwarts such as the KKK, but the American forces are massacred by “a race alien alike to every sentiment and association of American life.” Christianity is outlawed, and the United States becomes a province of the Chinese empire. Like many dystopian novels, The Last Days of the Republic ends on a cautionary note to present-day leaders, bemoaning the partisan divisions and politics of personal gain that prevented decisive action on the Chinese threat, and warning of an almost inevitable outcome.

The very name of the United States of America was thus blotted from the record of nations and peoples, as unworthy the poor boon of existence. Where once the proud domain of forty States, besides millions of miles of unorganized territory, cultivated the arts of peace and gave to the world its brightest gems of literature, art and scientific discovery, the Temple of Liberty had crumbled; and above its ruins was reared the colossal fabric of barbaric splendor known as the Western Empire of his August Majesty the Emperor of China and Ruler of all lands.

The book’s hateful message was popular, and the dystopian genre began to swell in close synchronization with surging anti-Chinese sentiment in the United States. Soon, this wave of fear and hate prompted the government to propose and pass an escalating series of legal obstacles to Chinese immigration and the naturalization of Chinese immigrants who had already entered the country. The legal arguments in these cases often directly echoed the language of dystopian fiction.

[i] Kansas Weekly Herald, Hiawatha, Kansas, Thursday, May 31, 1877. Page 4.

[ii] The San Francisco Examiner, San Francisco, California, Saturday, April 22, 1882 page 1

I had no idea that this precursor wave of Camp-of-the-Saints-like fiction existed in the case of 19th c. Chinese immigration, and I appreciate your bringing it to attention with this post. I wonder whether there was any pre-Civil War precursor associated with the anti-Catholic (especially anti-German/anti-Irish) Know-Nothing movement. Looking forward to the sequel.

Looking for more information on the books you list as "portraying Chinese immigrants as a fifth column" that would "destroy American culture and values," I found that "The Yellow Wave" is actually about a supposed Chinese immigrant invasion of Australia, not the US. Perhaps it had influence in the US, but it was published in Britain. "Under the Flag and Cross," which I could find no access to directly, seems not to be specifically anti-Chinese, as multiple descriptions I found say it recounts a "Japanese-Mongolian" invasion. (Since in 1908 all of Mongolia was still part of the Chinese empire, perhaps that means "Japanese-Chinese," but it's not a slam-dunk as a book about "Chinese immigrants.")