Dystopia and the mainstreaming of anti-Asian racism, part 2

What do the Chinese Exclusion Act, Jack London and Buck Rogers have in common?

Read Part 1 here (note that I changed the headline to be more descriptive)

In 1882, two years after The Last Days of the Republic hit book stands, the Chinese Exclusion Act was passed by the Congress and signed by the president, severely restricting immigration from China for 10 years.

“The Chinese are peculiar in every respect.” said John Sherman, a senator from Ohio, during the floor debate, echoing the language of slavery as well as phrases found in Atwell and Dooner. A 10-year extension in 1892 extended restrictions on immigration and citizenship to any “Chinaman” or “person of Chinese descent.” In 1902, the law was made permanent. It would not be fully repealed until the 1960s.[i]

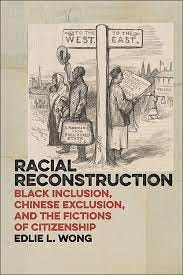

As literary scholar Edlie Wong chronicles in Racial Reconstruction, an important book on race and citizenship, the fictional framing of a Chinese invasion informed legal battles over the Exclusion Act, invoking the conceit of a “war” in order to defend and justify the Act and its successors.

These popular fictional works warned of apocalyptic consequences if Chinese immigration was not stopped, and lawyers for the government adopted their framing to turn back challenges by Chinese immigrants targeted by summary deportation and denial of the “right of return,” which deprived legal Chinese immigrants of the right to visit their homeland and then come back to America.

Contemporary court rulings, still occasionally cited in modern times, characterized immigration in words that could have been lifted from the florid dystopian fiction of the day—“foreign aggression and encroachment” in the form of “vast hordes… crowding in upon us.”[ii] Much of this language echoed and some may even have been appropriated directly from The Last Days of the Republic, which repeatedly cited the risk of Chinese “hordes” and China’s “plan of encroachment.”[iii]

These draconian steps were not sufficient to quell the rage stoked by racist fear-mongers. Chinese immigrants were targeted by White citizens with riots, vigilante violence and massacres all over the country. In 1871, hundreds of people mobbed and lynched 20 or more Chinese immigrants in Los Angeles. In 1885, White miners rioted and killed at least 28 immigrant co-workers in Rock Springs, Wyoming. In 1885, a White mob drove all people of Chinese descent out of Tacoma, destroying their homes, with the riot praised as a triumph in the next day’s newspapers. There were many more attacks.[iv]

Soaring xenophobia ensured an audience for more xenophobic fiction, a vicious circle. The biggest name to jump on the bandwagon was Jack London, best known as the adventure writer who penned The Call of the Wild (1903). In 1910, London published a short story titled The Unparalleled Invasion, foretelling the rise of an imperial China, which spread its racial menace through prolific procreation, a racial trope still attached to immigrants today. As London wrote:

The real danger lay in the fecundity of [China’s] loins, and it was in 1970 that the first cry of alarm was raised. For some time all territories adjacent to China had been grumbling at Chinese immigration; but now it suddenly came home to the world that China's population was 500,000,000. She had increased by a hundred millions since her awakening. … [T]here were more Chinese in existence than White-skinned people.

In the story’s conclusion, an American scientist invents a potent biological weapon, which is employed to genocidal effect by the U.S. and its European allies. The population of China is decimated by an engineered plague, and most of the few survivors are butchered by an invasion force, leaving the empty country to be resettled “according to the democratic American programme.”

While most of these works did not endure past the early 20th century, one memorable exception will be familiar to modern audiences—the tale of an American WWI veteran, Anthony “Buck” Rogers, who is accidentally exposed to a gas that puts him in suspended animation for 500 years. On waking, Rogers finds that the United States has been conquered by the Chinese, its civilization erased, with only a small contingent of resistance fighters maintaining a guerilla war from rural camps in areas reclaimed by wilderness.

Buck Rogers stories were more post-apocalyptic than dystopian, since they were not especially political. Asians—described variously as Mongols, Chinese and Han Chinese—are simply convenient villains, depicted in grotesque racial caricatures that were common in early 20th century media (such as the 1943 Batman serial, which featured a stereotypical Japanese villain portrayed by a White actor and narration that praised the internment of Japanese Americans).

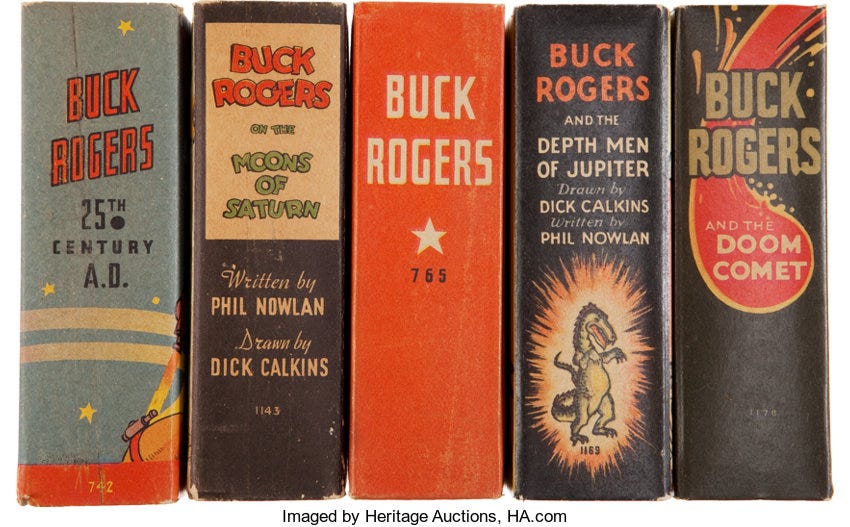

Buck Rogers first appeared in a 1928 novella, Armageddon 2419 A.D., but the character’s popularity exploded, with a swift sequel, The Airlords of Han, then continued for decades, thanks to a movie serial, newspaper comic strips, comic books and multiple television series.

Although the early newspaper strips featured Asian villains depicted in racial caricature, the story was largely sanitized of its “yellow peril” origins when it made the leap to the big screen. In a 1939 movie serial, Rogers fought a global criminal cartel led by a brutal dictator named Killer Kane, who had been created for the comic strip. Later iterations of the story traveled even further from its racist roots, putting Rogers into generic conflicts with assorted terrestrial and extraterrestrial threats. However, at least one author took advantage of the expired copyright of the original books to self-publish two obscure sequels in the 2000s, reviving the “Chinese Han” as racial villains who were descendants of non-human extraterrestrials.

[i] https://history.state.gov/milestones/1866-1898/chinese-immigration

[ii] Wong, Edlie L. Racial reconstruction: Black inclusion, Chinese exclusion, and the fictions of citizenship. NYU Press, 2015. https://amzn.to/42bDvLJ

[iii] Dooner, P. W. (1879). Last Days of the Republic. Alta California Publishing House. Pps. 65, 82, 124, 164, 209, 240.

[iv] https://www.tacomamethod.com/mapping-antichinese-violence

These two posts on anti-Asian dystopia are great!

In a class I teach on race and ethnicity in American culture, I have used London's The Unparallelled Invasion a few times, and I often use Gordon Chang's article "Eternally Foreign," which reviews some of the yellow peril novels discussed here. Exciting articles like these would really keep students' attention alongside those other more time-consuming texts. I love the Buck Rogers part--I watched some of that as a kid but of course in the most clueless way.