Constructing Whiteness

The decades-long struggle to legally define "white persons" an in-group

My recent posts on agency in extremist narratives are part of my medium- to long-term focus on the concept of lawful extremism. I’ve already discussed some issues pertaining to racial slavery in the United States. Today I want to look at the “prerequisite cases,” a series of legal rulings that made race a prerequisite for naturalized citizenship in the United States from 1878 through 1952.

From the nation’s founding through the Civil War, U.S. naturalization law restricted citizenship to “free white persons.” After the abolition of slavery, naturalization was opened to people of African descent, a revision explicitly understood to exclude people whom American society recognized as neither White nor Black.

I have been working with primary sources, following the corpus of legal rulings discussed in the landmark book White by Law by Ian Haney López, which I strongly recommend to anyone interested in this topic.

The first prerequisite case was brought by a Chinese immigrant named Ah Yup, who argued that Chinese people were White and thus eligible for naturalization. The court did not agree. You can read the full text of the ruling here. I have broken it down into terminology that will be familiar to those of you who follow my work. The chart below quotes the ruling (including archaic and offensive racial terms used by the judge) and associates the terms from the text with their corresponding social identity concepts.

Putting aside for the moment what I expect to be a highly contentious argument about whether immigration exclusions can be definitionally extremist, you can see here the classical elements of an extremist system of meaning, as defined by Haroro Ingram, whose work I have cited here in the past. Chinese immigration is described as a crisis, for which the solution was to ban Chinese people from admission to the American citizens in-group, which was restricted by law to White and Black people.1

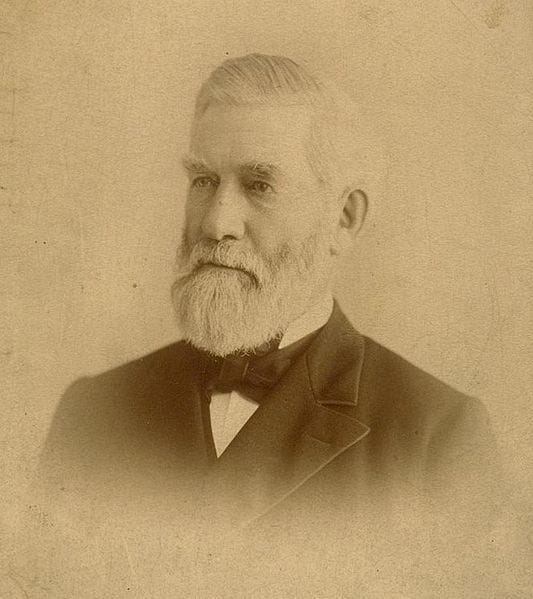

In this chart, I’ve again added a category to Ingram’s system—in-group boundary. In any identity-based ideological or legal construct, a key problem is defining the boundary between in-group and out-group, aspects of which I’ve mentioned previously. The in-group boundary is the chief concern of Lorenzo Sawyer, the judge in Ah Yup, who is attempting to formulate a legal definition of “white person.”

He approaches the problem from two fronts. The first front, which Sawyer would describe as “scientific” and I refer to as a “appeal to authority” reflects the now-discredited race science of the day, complete with citations to various well-known taxonomies of race. Ideological appeals to authority typically include texts, such as the dictionary and encyclopedia cited in Ah Yup, and scholars or scientists, three of whom are cited in the opinion. Unlike ideological appeals to authority, Sawyer takes a very minimal approach to summarizing the authority’s findings. In part, this is because Sawyer is using the appeal to authority as a way to avoid advancing a personal theory of race, unlike movement extremists, who are often happy to tweak or misrepresent the contents of the authorities to which they appeal.

Since this is a court case, a third authority is cited—Congress, the legislative body that passed the naturalization law in question. In addition, Sawyer cites the legislative debate around the naturalization act, which he says made clear that the legislators wrote the law in a manner explicitly meant to exclude Chinese people, even if they didn’t stipulate as much in the law’s text.

Perhaps more definitively, the ruling cites what Haney López calls “common knowledge” arguments, and which I refer to as in-group consensus. A member of the White in-group himself, the judge might not know how to define the White racial category, but he knows it when he sees it, and he expects that everyone else does too. In Sawyer’s words, White is a valid legal category primarily because its meaning is so apparent “as ordinarily used everywhere in the United States” that “one would scarcely fail to understand” what it meant. According to Sawyer, the meaning of “white person” was “well-settled” in “popular speech” as well as being “universally understood” by the law’s Congressional authors as exclusionary toward Chinese people. Haney López notes that a later prerequisite judge described “white” as the government’s way “to designate persons not otherwise classified.”

Unsurprisingly, Ah Yup lost the case. But, as Haney López notes, “scientific” efforts to categorize various peoples of the world according to race were slowly exposed as meritless in the years that followed. Because of this, in-group consensus arguments came to dominate legal theories of race until Congress eventually passed a law ending race-based naturalization. While that event was not certainly not the end of racial classification in law, it was the last of this particular body of cases that repeatedly sought and largely failed to draw bright lines around White identity.

Down the road a little bit, I will start trying to contextualize this and other historical examples in comparison to extremist ideological frameworks. I can see a number of parallels in the quest to define White identity in the legal system and the parallel effort in British-Israelism, which I documented in a 2017 paper. Points of comparison and contrast include their respective appeals-to-authority and legitimacy challenges.

Legitimacy challenges are especially interesting in that they’re inherent to the courts, which may lead to ideological evolutions more likely to favor the status quo. In movement extremism settings, beliefs may be more likely to shift and change mutate in dramatic and unexpected ways.

To be continued…

As Haney López notes, none of the plaintiffs in the prerequisite cases attempted to mount an argument that they should be considered Black. While this was partly driven by some obvious factors having to do with the status of Black people in the United States during this period, it’s also worth noting that the naturalization law did not identify “Black” as a category but rather specified that naturalization was open to people born in Africa or of African descent, a more clearly delineated criterion that most plaintiffs could not meet.