Welcome back to World Gone Wrong. If you’re just tuning in:

This week, we’re picking up where last week left off, with a look at how extremist narratives can change when extremist movements have true agency—in other words, what do narratives look like when the extremists are in charge.

I want to stress that this article, like those preceding it, represents a work in progress. By the time I get to the end of the road (i.e., my completed dissertation and beyond), some of these ideas will likely evolve. For reasons that are probably sadly obvious, I’m increasingly interested in the question of how extremism operates from positions of power or popular support.

One particularly well-documented example of what I sometimes refer to as “extremism from the center” is the practice of racial slavery in the United States. Many academic and policy definitions argue that extremism can only occur on the fringes of society, and the converse position, which is that a society’s dominant culture cannot be extremist. I argued against this at length in my book, Extremism, and the definition I put forward in that book is designed to capture extremist movements regardless of their position in the power structure. Extremism is:

The belief that an in-group’s success or survival can never be separated from the need for hostile action against an out-group.1

Under this definition, the ideology that supported racial slavery in the United States clearly qualifies as extremism. And it was indeed an ideology, constructed over the course of centuries, with a dramatic acceleration in ideological innovation taking place in the 19th century, as the practice of slavery came under heavy challenge. In the words of American historian Drew Gilpin Faust:

Although proslavery thought demonstrated remarkable consistency from the seventeenth century on, it became in the South of the 1830s, forties, and fifties more systematic and self-conscious; it took on the characteristics of a formal ideology with its resulting social movement. The intensification of proslavery argumentation produced an increase in conceptual organization and coherence within the treatises themselves, which sought methodically to enumerate all possible foundations for human bondage[.] (Faust, 1981)2

I have written elsewhere about the proliferation of ideological features in the face of a serious challenge to legitimacy. Legitimacy challenges cause an increase in both the volume and complexity of extremist beliefs.3 With its legitimacy under siege, the proslavery movement crafted ever more elaborate defenses, evolving and detailing White supremacist narratives that would endure long after the last slave was freed.

All of the ideological defenses of slavery were unanimous in arguing that the United States, and sometimes the White race, could not succeed or survive without the perpetual enslavement of Black people. But beyond that unifying principle, the arguments were wildly varied and sometimes incompatible. The proslavery argument typically contained at least two of the following three components:

The United States was economically and politically dependent on slavery.

Slavery had been a generally acceptable practice throughout history.

White people were superior to Black people, justifying a racial hierarchy.

There were three major thrusts of argument, which usually overlapped:

Secular-pragmatic: This argument usually focused on economics , arguing the United States economy would collapse in the absence of slavery.

Secular-scientific: Proponents of so-called scientific racism attempted to put a veneer of rationality over racist beliefs, arguing that White enslavement of Black people was part of the natural scientific order of the world.

Religious: This category includes a dizzying welter of often-incompatible interpretations of the Bible and non-canonical historical religious sources.

I will, eventually, publish some detailed analyses of select antebellum pro-slavery narratives, but for now I want to approach it from 60,000 feet to talk about agency. It should be clear to everyone that White antebellum slaveowners wielded total agency over their out-group, Black people. The pro-slavery argument in all its variations ultimately boiled down to an assertion that White people could never be secure or successful unless they enslaved Black people.

If it is not obvious, you need only consult the landmark 1856 Supreme Court decision in Dred Scott v. Sanford, a test of the constitutionality of slavery. The Court affirmed that in America, a “free negro of the African race, whose ancestors were brought to this country and sold as slaves, is not a ‘citizen’ within the meaning of the Constitution of the United States” and even further that Black human beings “had no rights which the white man was bound to respect; and … might justly and lawfully be reduced to slavery for his benefit.”

It’s worth looking at the quote in a fuller context:

They had for more than a century before been regarded as beings of an inferior order, and altogether unfit to associate with the white race, either in social or political relations; and so far inferior, that they had no rights which the white man was bound to respect; and that the negro might justly and lawfully be reduced to slavery for his benefit. He was bought and sold, and treated as an ordinary article of merchandise and traffic, whenever a profit could be made by it. This opinion was at that time fixed and universal in the civilized portion of the white race. It was regarded as an axiom in morals as well as in politics, which no one thought of disputing, or supposed to be open to dispute; and men in every grade and position in society daily and habitually acted upon it in their private pursuits, as well as in matters of public concern; without doubting for a moment the correctness of this opinion.4

This social precedent was endorsed by the Supreme Court in a decision that accelerated the drive toward Civil War, eventually overturned by the 13th and 14th Amendments. The Dred Scott decision is one of the most important articulations of “extremism from the center,” arriving to reinforce the status quo in the face of a groundswell of popular and principled opposition to slavery.

I want to highlight one line from the paragraph above: “For his benefit.” The construction of the sentence suggests that the phrase is meant to refer to the Black person, rather than the White person. While this sounds ludicrous to modern sensibilities, White proslavery extremists overwhelmingly and repeatedly argued that slavery benefited Black people.

Modern conversations about extremism, especially in the post-9/11 era, focus on how extremist rhetoric endorses hostility or hate toward an out-group. In part, that’s because we mostly talk about “extremism from the fringes,” rather than extremism from the center. Fringe extremist groups seek to overturn the status quo, typically arguing that they must protect their eligible in-group from an out-group by harming or killing the out-group, or expelling it from the territory of the in-group.

If an extremist group or movement possesses the agency that comes with occupying the center of society, its calculus changes. Majority and/or status quo extremists make their arguments from a position of power. The tenor of those arguments are much different than fringe arguments. When we interrogate why that is the case, we come to an incredibly important distinction with regard to agency: Status quo extremists seek to demobilize opponents, while fringe extremists seek to mobilize supporters.

Status quo extremists seek to demobilize opponents,

while fringe extremists seek to mobilize supporters.

It’s important to understand the context in which the debate over slavery played out—almost entirely White, and almost entirely racist. You can find a fuller discussion in Ibram Kendi’s Stamped From the Beginning and elsewhere, but its relevance to this discussion pertains to the ideological narratives in defense of slavery.

Relatively few abolitionists believed in racial equality as we today understand it, meaning full participation in every aspect of society. Many abolitionists simply abhorred the specific practice of slavery while still believing that Black people were inferior to White people. Thomas Jefferson, for instance, talked a good game on abolition while still keeping slaves and even finding time to write a “scientific” treatise on Black inferiority that would fuel proslavery arguments long after his death.5 Abraham Lincoln opposed slavery but initially argued that upon abolition, all Black people should be “repatriated” to Africa.

I raise these examples to clarify the context of proslavery arguments. The defenders of slavery were speaking to White audiences who did not need to be convinced of White superiority. The central criticisms of slavery revolved around the cruelty of the practice, rather than a desire to establish equality. Proslavery ideologues wrote primarily to justify the existing practice of slavery, but in doing so, they crafted key racist concepts that continue to find adherents even today.

The simpler aspect of the proslavery argument was pragmatic, or rather, that’s how it sought to appear. Proslavery ideologues argued that slavery was necessary to maintain the American economy and way of life. This was a simple status quo argument, and now that slavery-as-status-quo has passed out of living memory, we can see its obvious wrongness and failure.

The more insidious part of the proslavery argument was the “positive good” argument, a phrase that first appeared in 1819 and was immortalized on the floor of the U.S. Senate by John C. Calhoun of South Carolina, in an 1837 response to abolitionist petitions before Congress.6

Calhoun’s speech was squarely aimed at the eligible in-group, a statement of defiance from “the South” (proslavery) toward “the North” (antislavery), warning that any concessions by the former would lead to a “slippery slope” and ultimate defeat. Calhoun’s argument was firmly based in racism, presuming the superiority of White people to Black people, but he took issue with another senator’s earlier comment characterizing slavery as a “lesser evil” in comparison to emancipation. “I hold that in the present state of civilization, where two races of different origin, and distinguished by color, and other physical differences, as well as intellectual, are brought together, the relation now existing in the slaveholding States between the two, is, instead of an evil, a good—a positive good,” Calhoun said.

Although Calhoun wove various social and economic critiques into his comments, his core argument was relatively simple. Black people, he speciously claimed, had a higher quality of life as slaves than they would if free. “Never before has the black race of Central Africa, from the dawn of history to the present day, attained a condition so civilized and so improved, not only physically, but morally and intellectually,” he said without evidence. The arrangement was also good for White people of European descent, he claimed, praising the “virtue, intelligence, patriotism [and] courage” of Southern slaveholders, who had not “degenerated” because of the practice.

There’s more, but you get the gist. The thing to remember about Calhoun’s argument is that it was far from unique. The positive good argument owed much to secular identity construction narratives, which sought to “scientifically” prove that Black people were, due to their intrinsic nature, happier and healthier in conditions of bondage, but the religious argument made similar assertions.

Three Judeo-Christian racial theories took on especial prominence. The first, and more widely adopted, was the “Curse of Ham.” The Bible includes a story in which Noah’s three sons come across him drunk and naked. Japheth and Sham avert their eyes and cover their father, but Ham is disrespectful. When Noah wakes up, he curses Ham’s son as a punishment. “Cursed be Canaan; a servant of servants shall he be unto his brethren” (Genesis 9:25). Proslavery ideologues crafted elaborate arguments that the curse changed the skin color of Ham’s progeny from White to Black and condemning his descendants to slavery. The second theory held that Black skin was the Mark of Cain, inflicted as God’s punishment for killing his brother Abel. (Genesis 4:1-25) Finally, a smaller number of religious arguments held that Black people were not human at all, but descended from a pre-Adamic race, a claim that stands as precursor to the modern Christian Identity movement.7 While this angle was less widely circulated, it was adopted by very prominent proslavery activists, including Jefferson Davis, the first and only president of the Confederacy.8

The proslavery faction held powerful agency over much of the United States. Slavery was the status quo in America, so entrenched that it could be overturned only by war. Thus, scientific and religious defenses of slavery sought the same outcome—to demobilize the opponents of slavery, rather than to mobilize its supporters, who were already engaged in ideologically mandated hostile action toward the out-group. Their arguments may look strange to those of us accustomed to modern fringe extremist ideologies, but the defense of slavery contained all the elements of extremism. The proslavery case, in its very broadest iteration, claimed:

The White eligible in-group was superior to the Black out-group

The health and success of the White in-group was inseparable from hostile action (enslavement) against the Black out-group

These arguments are familiar enough in the context of modern extremism. But they were joined by a third argument, that sought to deny the extremist nature of slavery by denying the hostile nature of the action mandated against the out-group.

Enslavement of the Black out-group should not be considered a hostile action for one or both of the following reasons:

God specifically decreed that the White in-group should enslave the Black out-group. By shifting responsibility to God (and circuitously to sinful Black progenitors like Ham and Cain), the White in-group is absolved of hostile intent.

Science proved that the Black out-group was happier and healthier under conditions of enslavement. Under this argument, White in-group members were depicted as caring and nurturing masters who provided necessary structure to the lives of members of the Black out-group, again absolving the in-group of hostile intent. Slavery, in this context, was a “positive good.”

Needless to say, this argument was entirely specious, and no one at any point proposed that the enslavement of White people was even imaginable, let alone that it could be considered good for White people.

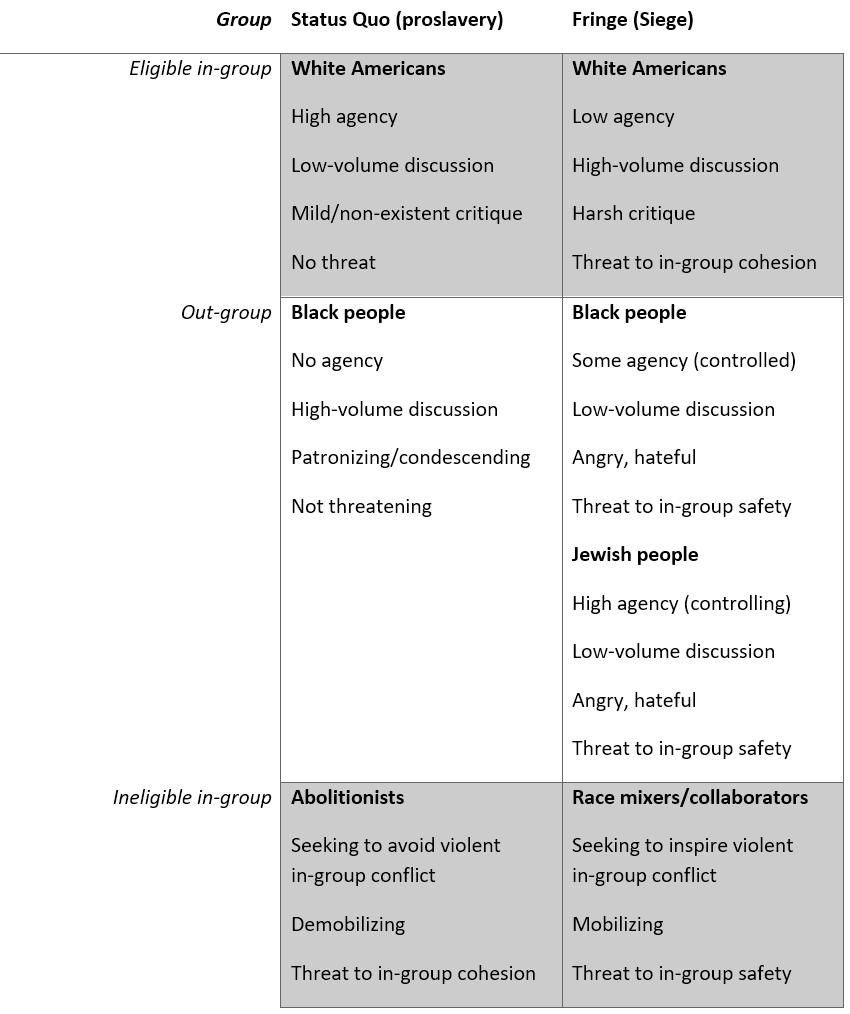

One of the notable ways that these ideologies depart from modern fringe ideologies is that proslavery ideologies spent much less time analyzing the White eligible in-group than modern White supremacists like James Mason, the author of Siege, whose work is overwhelmingly weighted toward a critique of the in-group.9 (Readers who are not familiar with my paper on Siege may find it helpful to inform and support the next few paragraphs.)

Proslavery ideologues took a much gentler approach to the in-group, mostly trying to deescalate conflict between the proslavery extremist in-group and the antislavery ineligible in-group, although there were some exceptions. Instead, proslavery ideologies are overwhelmingly weighted toward defining the out-group using the specious religious and scientific arguments discussed above. When abolitionists are discussed, they are often (but not always) referred to in relatively respectful terms, as people who may have good intentions but hold misguided views. The proslavery argument seeks to convince the abolitionists—or those who might be swayed by their arguments—to stand down. This was typically approached in reconciliatory terms, but included a warning that continued ineligibility will lead to war. This rhetoric heated up as the Civil War drew near, but secession and war (a tangible break in the cohesion of the in-group) are almost always discussed as preventable tragedy rather than desirable outcome.

Here’s a brief summary of the major proslavery arguments, compared to modern neo-Nazi arguments. Note that the proslavery column is my assessment of the general thrust of the genre, which for the limited purposes of this discussion papers over a lot of context-dependent variation, such as the escalation of commentary in the runup to secession. My dissertation will dive deeper on these topics.

To conclude, for the moment, the question of extremist agency is not simply confined to the pages of an ideological tract. Extremist narratives ascribe agency in various ways, but extremist movements also possess agency in the real world. Fringe movements seek to portray themselves as having higher agency than the eligible in-group when acting against the out-group, but their real-world agency is dependent on mobilizing members of the eligible in-group, and their rhetoric aligns with that goal.

When the extremist in-group is the in-group’s dominant status quo movement, the extremist in-group has true agency over the eligible in-group. All extremist in-groups seek to dominate the eligible in-group. For status quo movements, that goal is a fait accompli, and so its rhetorical focus shifts to diminishing the agency of the ineligible in-group, which threatens to upset the status quo. Ineligible in-group members are only assigned to the out-group after efforts at reconciliation have failed.

Returning to the question that prompted this series, do perceptions of agency (real or imagined) affect how extremist groups target their hostile action? I don’t think we can generalize this question, and I don’t see clear correlations. A number of confounding variables need to be examined, including:

Does the extremist in-group possess actual agency over the out-group?

Does the extremist in-group possess actual agency over the eligible in-group?

Does the extremist in-group seek to preserve or overturn the status quo?

Relatedly, and I may touch on this somewhere down the road, I think that momentum is a very important and under-analyzed aspect of this question. The proslavery movement represented the status quo, to be sure, but it was a waning status quo. The writing was on the wall. In the run-up to the Civil War, the most fecund period of proslavery ideology creation, proslavery arguments sought to seize the high ground by depicting themselves as the moderate protectors of in-group cohesion.

When an extremist movement is waxing, the calculus once again changes, still differing from most modern fringe movements. Without launching into an entire new article, I would end by encouraging you all to think about two specific waxing extremist movements—the Nazi Party in the 1930s and 1940s, and ISIS starting in 2014 and continuing through the collapse of its territorial caliphate. In my book, I listed various types of crisis found in extremist narratives, one of which was “triumphalist.” Waxing extremist groups are perhaps the most dangerous and unpredictable, emboldened by their success at wresting agency from the eligible in-group, openly embracing and escalating the violence of their hostile actions against both out-groups and ineligible in-groups, while harshly policing eligible in-group members within their domain—as with the adoption of the Nuremberg Laws in 1935.

Food for thought, and for another day. If you’ve made it through all of this, thanks for reading, and I promise the next newsletter will be shorter and less academic-y.

Berger, J. M.. Extremism (The MIT Press Essential Knowledge series) (p. 134). MIT Press. Kindle Edition.

Faust, Drew Gilpin, ed. The ideology of slavery: Proslavery thought in the antebellum South, 1830–1860. LSU Press, 1981. Kindle Edition, p. 3.

Berger, J.M. “Extremist Construction of Identity: How Escalating Demands for Legitimacy Shape and Define In-Group and Out-Group Dynamics”, The International Centre for Counter-Terrorism – The Hague 8, no. 7 (2017). https://icct.nl/app/uploads/2017/04/ICCT-Berger-Extremist-Construction-of-Identity-April-2017.pdf

Finkelman, P. (2019). Defending slavery: Proslavery thought in the old south: A brief history with documents. Macmillan Higher Education. Kindle Edition. p. 119.

Extremist Construction of Identity.

Davis, J., Rowland, D. (1923). Jefferson Davis, constitutionalist: his letters, papers, and speeches. Jackson, Miss.: Printed for the Mississippi Dept. of Archives and History. Vol. 4, p. 256-258.

Berger, J.M. A Paler Shade of White: Identity & In-group Critique in James Mason’s Siege. Washington, D.C.: RESOLVE Network, 2021. https://doi.org/10.37805/remve2021.1. https://resolvenet.org/research/paler-shade-white-identity-group-critique-james-masons-siege