It was madness, in retrospect, the notion that we could shepherd millions or even billions of people who had nothing in common into a single venue with a mandate to loudly express themselves, and trust that it would somehow work out for the best.

It’s a miracle it lasted as long as it did.

I was tempted to end the newsletter right there, because what else is there to say? Web 2.0 is coming to an end, and it’s not clear what will take its place.

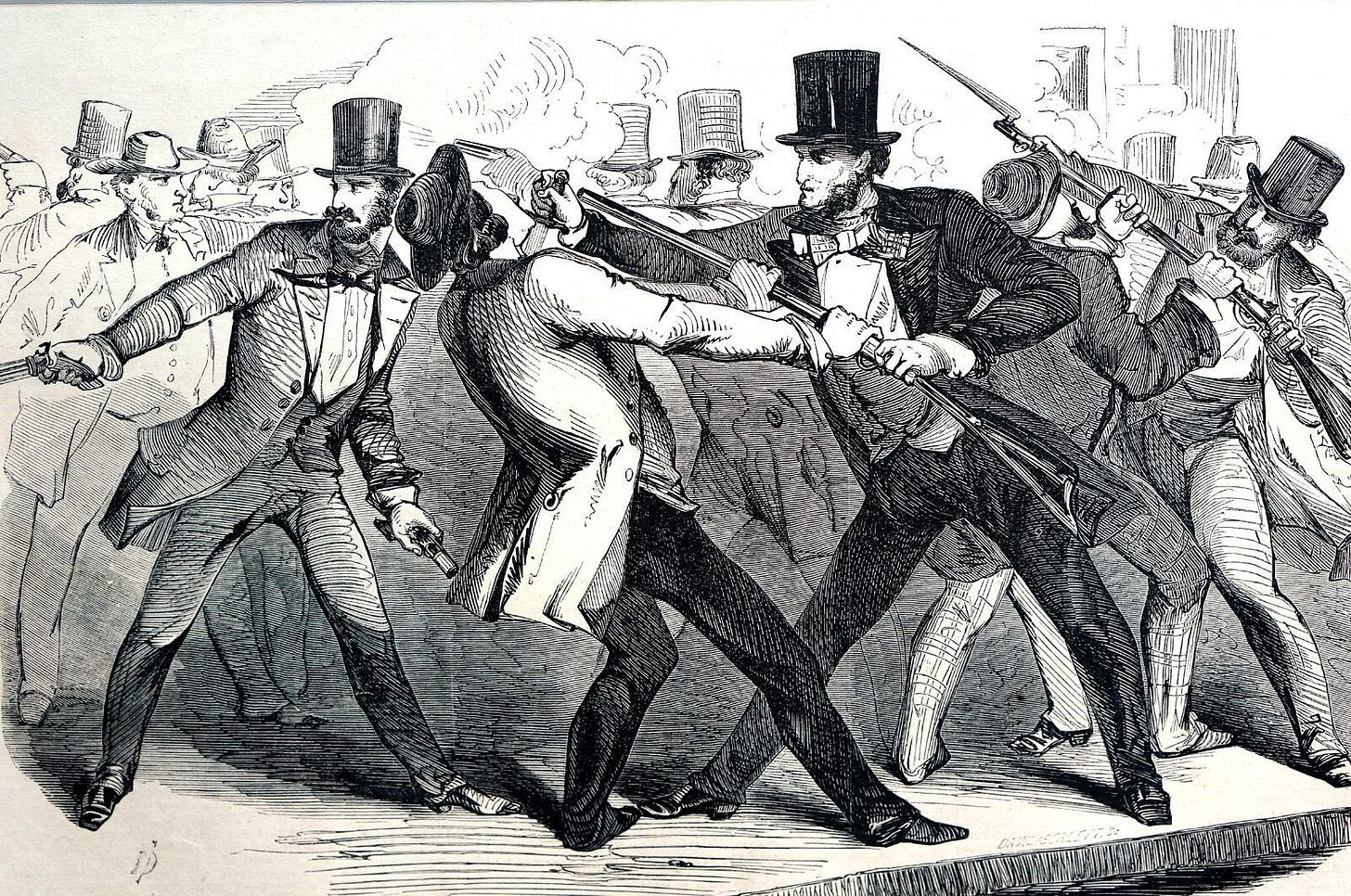

The slo-mo collapse of Twitter and possibly faster fall of Reddit are symptomatic of wider problems. Web 2.0 has always been, was always going to be, messy. User-generated content inevitably reflects users, and while I choose to believe the majority of people are decent, those who aren’t have become adept at capturing our attention. The majority of people are tired. The majority of people don’t need this shit.

There’s little reason to hope that the many would-be Twitter-killers will come to a better end. Mastodon has been around for some years, but it hasn’t been able to fully exploit the opportunity presented by Twitter’s decline and fall, in part because it deprecated features (search, quote tweets) that made Twitter fun and useful but were also widely employed to perpetrate abuse. The typical user doesn’t (and won’t ever) know or care about federation and decentralization, the main selling points of Mastodon. They care about user experience.

Post News, as far as I can tell, continues to underperform. The most recent posts in my feed are always counted in hours, if not days. When I try to discover new follows, I find little of interest. Substack Notes is also low volume, but high on sealioning, which is not really a selling point. Bluesky is more fun, at least when it’s not a circular firing squad, but still not very usable for work. And its content moderation approach (still not quite ready for prime time after a recent update) doesn’t look like it will scale when the platform goes wide, meaning bad people are likely overrun the place in short order.

What else? Facebook feels like some weird vestigial organ, like tonsils or an appendix. It’s probably doing something for you, but would you really miss it? The rest is video, which, fine, pivot there if you want, but I need a text feed.

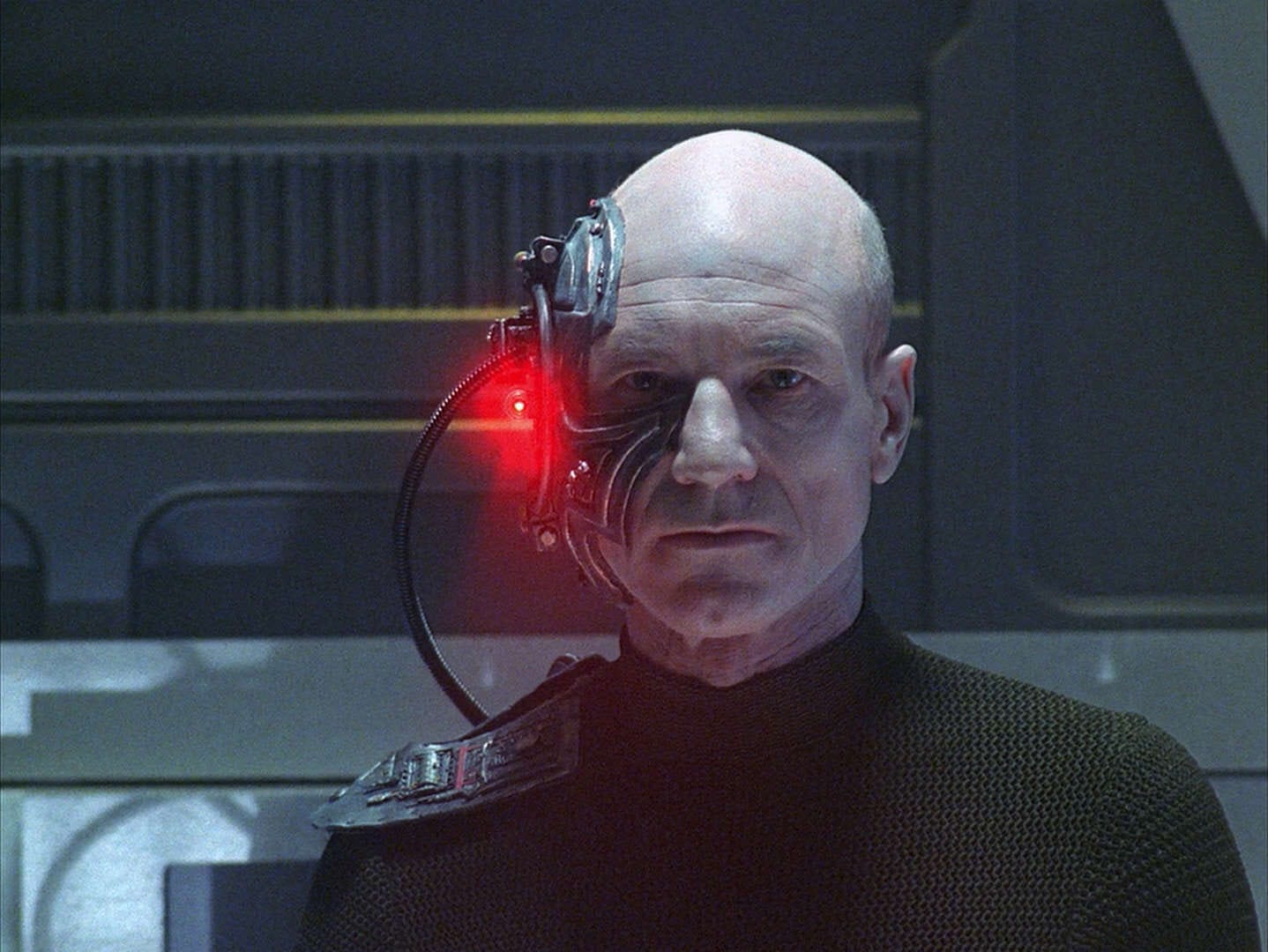

Unfortunately, Web 3.0, inasmuch as the phrase means anything at all, looks to be even worse. Blockchain and crypto barely got started before they went into freefall. The decentralization/federalization evangelists will try to explain how 3.0 magically empowers free speech without creating huge new opportunities for abuse. I don’t buy it. Meanwhile, the fight to define Web 4.0 has already started, but it’s a lot of frankly worrisome hype about “symbiosis between people and computers” or “merging offline and online” or “AI something something,” all of which sounds wretched. At best prone to the same problems Web 2.0 had; at worst, well...

So where does that leave us? Cross-posting across four or five different platforms for half the reach that we had on Twitter? Retreating to our group chats, or god forbid, our IRL neighborhoods? At least in those spaces, we have some shared interests.

Maybe relationships just don’t scale.

Would you go to a party where you know 1 percent of the people? 0.1 percent? 0.001 percent? Would you be comfortable walking into a stadium full of people from all over the world and striking up conversations at random? What if an algorithm suggested people for you to talk to?

Obviously social networks aren’t quite like this. They’re more structured, with tools that theoretically connect people over common bonds. But the problem with most Web 2.0 platforms is that you end up spending a lot of time hearing from total strangers, some of whom are hostile to you personally, or your identity group, or your way of life. Some strangers are safe to be around. Some are not. Some strangers can be trusted to convey accurate information. Others can’t.

Algorithms drive much of this activity, sometimes with good results, often not. Do you really trust a Silicon Valley engineer to reliably connect you with people you like? Anyone who’s been set up on a date by a friend will have doubts. If the people who know us best can’t reliably connect us to other people, why should an algorithm?

We grapple with so many questions around online safety and social media that we can lose sight of the forest for the trees. Maybe human communities are simply not equipped to scale indefinitely . Maybe our social brains need the structure that arises from limitation—smaller groups in motion around geographies or particular shared experiences. Smaller groups that meet and merge more easily with other smaller groups. Groups that clash or cooperate based on real-life events, rather than felt ideologies operating over global distances.

The dog whistle of (((globalism))) is a thin disguise for racism, but the choice of disguise says something. Yet the people who use the term, who dread and loathe the idea of some imagined one-world government, are perfectly happy to accept the existence of a one-world online conglomerate. They will post and post and even fight to the (rhetorical and sometimes literal) death for control of it.

Who decided it was a good idea to empower every single one of us to reach out to any other person or massive groups of people at any time over any distance? Federation, for all its flaws, is one way to think about slicing the world into smaller, more manageable pieces, but it retains the impulse to connect everyone, the phantasmal dream of global scale.

The ideology of growth in Silicon Valley is anathema to smaller approaches. The latest generation of the masters-of-the-universe trope have built their empires on the promise of extracting profit from one unitary channel that includes everyone in the whole world and touches every person at every waking moment. They need human systems to scale because that’s the only way they can extract profits at an acceptably astronomical level. Even if our brains are built to handle the complexity of a globally interconnected experience, the overlapping networks are so densely layered that emergent behaviors are bound to overcome even the best of intentions.

Maybe I’m wrong about this, and that’s OK. I am not sure I’ve even convinced myself. If you know me, you know I’ve been at this global connectedness game for a long time, not just as a student of it, but as an active “extremely online” participant.

And we live in a global village; there’s no sense in denying it. What happens in one part of the world affects every other part. That would still be true if the Internet went away tomorrow, although the pace of cause-into-effect would likely slow down.

The overlords of Web 2.0 are determined to burn and rave at close of day. They will not go gentle into that good night, but it would be better for all of us if they did. And maybe we would be healthier, happier people if we let them, instead of clinging to the golden promise of global connection that we once believed in.

Maybe we should sit with the question in its most basic form: Is human scale compatible with global scale? (Ahem, read Optimal.)

And if we decide it is not, how can we start building healthier, safer systems to protect and leverage human scale within a globally networked environment?

J.M. Berger is a Senior Research Fellow for the Center on Terrorism, Extremism, and Counterterrorism at the Middlebury Institute of International Studies. Opinions expressed here (and anywhere else) are his own.

(Also some of the people I followed tried Mastodon and were deeply unhappy with it so I have not even tried to figure out where or if everyone I followed was on there)

I thought that twitter was evil enough in the pre-Musk era and if I had to rely on it for all my news I would hang myself. But since I did not know where to start with this antiracism business I could follow exactly 2 people I knew and follow the trail from there. These sites are OK if they are treated as toy models of real life and real community but as stated in the post this will not make the shareholders any money.