There is a tyranny in the womb of every Utopia.

-- Bertrand De Jouvenel, French philosopher (1957)[i]

The history of dystopia opens with the tale of a world too good to be true. In 1516, Renaissance scholar Sir Thomas More published a short novel about a perfect society called Utopia. The name, derived from Greek, meant “no-place.” More described a conversation with a traveler who had returned from a far-off land of few laws and high virtue, said to be governed in accordance with the principles of the ancient philosopher Plato.

…having rooted out of the minds of their people all the seeds, both of ambition and faction, there is no danger of any commotions at home; which alone has been the ruin of many states that seemed otherwise to be well secured; but as long as they live in peace at home, and are governed by such good laws, the envy of all their neighboring princes, who have often, though in vain, attempted their ruin, will ever be able to put their state into any commotion or disorder.

The people of Utopia were well-fed, living in a communal system where all resources were shared. They did not lock their doors, because they had no thieves. Vice was rare. Health care was free. Elders were provided for. The citizens enjoyed freedom of religion, one of their most cherished values. Utopia’s leaders were elected. They detested war and killing, preferring to live in peace.

But there was a catch. There is always a catch.

By modern standards, certainly, Utopia was far from perfect. The nation practiced a (relatively benevolent) form of slavery, and women were kept in subsidiary positions. There were harsh punishments for fornication and adultery.

In 1516, these positions would not ruffle many feathers. But even by the standards of the day, something was amiss in the narrative. The traveler praises Utopia with deadpan gravity, urging the adoption of Utopian values throughout the world—but those values were very different from Thomas More’s fervent Roman Catholicism.

The Utopians practiced euthanasia on the seriously ill, for instance, an unconventional practice the Catholic Church had only recently stamped out in France through an extremely violent Crusade. Divorce was permitted, an odd inclusion considering More was later executed in part for refusing to acknowledge the religious validity of Henry VIII’s divorce from Catherine.

Scholars today are decidedly uncertain about More’s intent in writing Utopia, but some argue the book is a satire, its straight-faced endorsements of Utopia meant to be ironic, a pointed commentary on both contemporary European values and the impossibility of a perfect society. Even setting aside subtext, the moral of the book is ambiguous, and the narrative fails to answer whether Utopia’s vaunted comforts and placidity outweigh its values, which the author seemed to abhor.[ii]

In the seeds of history’s most iconic perfect society, dystopia already lurked. There is always a catch. The very concept of utopia invites consideration of its dark counterpart, like the snake in the garden, or the monster in the closet. In the words of Margaret Atwood, one of the greatest dystopian authors of all time, “within each utopia, [lies] a concealed dystopia; within each dystopia, a hidden utopia.”

Readers instinctively understood this, even in the 16th century. Utopia produced a wild and prolific backlash against the very idea of a perfect society. This initially took the form of anti-utopias, books that followed the same basic format, relating the adventures of travelers to strange and dysfunctional foreign lands. The best-known and least-derivative of these is Gulliver’s Travels by Jonathan Swift, published in 1726, but the genre was already well-established by that time.

Some anti-utopias took place in entirely fictional lands. A 1605 Medieval Latin satire titled Mundus Alter et Idem (“The Old World and the New”) featured a tour of lands with names such as Crapulia and Moronia, whose inhabitants and customs reflected their names. A number of anti-utopias were set in real, but unexplored, locations. The History of the Sevarambians (1675), described an Australia divided into warring kingdoms, one utopian and one dystopian.

The more modern conception of dystopia—in which current real-world trends play out badly in the not-too-distant future—started to emerge in force about 100 years after Utopia. With a few exceptions, stories about the future had mostly been limited to religious or mystical prophecy until the 17th century, when the genre of science fiction began to flower, driven in part by recent scientific discoveries about the universe that had opened minds to the possibilities for humanity over the longer term.

Dystopias were among the earliest examples of this future fiction. A six-page pamphlet titled “Aulicus his dream, of the Kings sudden comming to London” was published in 1644, inspired by the English Civil War that had started two years earlier, and is almost certainly the first unambiguous example of dystopian fiction set in the not-too-distant future. The story, narrated from a dream, forecasts a victory by the tyrannical King Charles I over the forces of parliamentarianism in stark, cautionary terms. Like many of the stories that would follow, the message warned against complacency and accommodation. Arising from his dream, the narrator declares he is finally awake to the danger but “all the City of London fast asleep.” He sings out a song of alarm to warn them of the coming treachery. “Be wise, and be not undone,” he concludes, delivering the warning embedded in all dystopias, it can happen here.

The format was slow to catch on, at first. The first proper dystopian novel was published in 1769 by a British journalist best known for his efforts to secure freedom of the press for political reporters. Initially published as Private Letters from an American in England to his Friends in America and later reprinted under the title Anticipation, or the voyage of an American to England, in the year 1899, the novel was a satire that described England’s future devolution into gaucheness and penury, while London has been reduced to a collection of ancient hovels in disrepair.

In a series of mildly humorous vignettes, the titular American letter writers describes how the Royal Society building has become home to a fish market, while the British Museum, brand-new in the author’s day, now lay in ruins, with boxing matches held in its gardens. St. Paul’s Cathedral is now a burlesque-style concert hall, and Christianity has become degenerate, with “indolent” priests earning their station through popularity and hospitality rather than knowledge. “Nobody outwardly disbelieves or opposes a gentleman at the head of his own table,” the correspondent reports.

The story is “tedious,” as the narrator frequently concedes, yet for readers of the day, there must have been a strange fascination in this detailed vision of society’s greatest achievements reduced to abandonment and desolation. The narrator provides a long litany of topical causes for England’s decline—not one big thing, but a host of small things, including corruption, high taxes and tariffs, and the cost of education, all of which led the kingdom’s best to emigrate abroad.

As one sorrowful resident sums it up, “I do most solemnly swear, that England may thank herself for all that she now suffers, and has for nearly a century past, by desertion of its inhabitants, migration of its richest merchants and transportation of all its favourite manufactures. … All of the good people of this country are now settled somewhere in America, and … only the scum and refuse of arts of every kind of science, are left behind.”

A handful of works in the vein of Private Letters were published during the 18th century, stories which were mostly dire lists of despairing developments, rather than entertainment in any meaningful sense. But the dystopian trickle became a flood at the start of the 19th century, with a commensurate increase in quality.

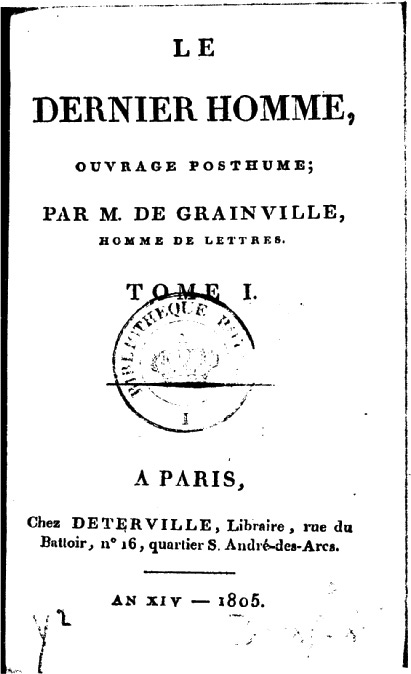

The new wave started with a French prose poem, Le Dernier Homme (The Last Man), published in 1805. A religious tale set in a far future world where declining human reproduction has reduced the population to a handful, the story features the last potent man and last fertile woman. The first man, Adam, is sent by God to convince the couple to let humanity die, leading to the Final Judgment. In a pattern that would be repeated throughout the history of the dystopian genre, this innovative work inspired a flurry of imitators, including a plagiarized English edition, spawning an entire category of “Last Man” poems and tales.

But in a rapidly modernizing world, politics, rather than religion, would fuel the explosive growth of the genre. Short and long dystopian works first emerged as a potent force in UK politics. The Reform Act of 1832—an effort to end corrupt parliamentary gerrymandering—inspired a series of competing dystopias depicting the disaster that would unfold in the not-too-distant future if the law was passed, or if it was not passed. An early proposal to build a tunnel under the English Channel led to a series of stories about French troops conquering England through the passage. Competing stories described the disaster of Irish independence and its utopian opposite.

Full-fledged novels soon emerged, in growing numbers. By the middle of the century, they were ubiquitous. “It is a curious thing, that there is scarcely a political or even a religious change possible in this country, but that there is a novel ready timed to the event,” wrote one book reviewer in 1852, in a discussion of The Last Peer, a dystopia lamenting the future decline of the British aristocracy.

Heated political arguments rapidly escalated the number of both utopian and dystopian stories available, as authors churned out derivative sequels, prequels and rebuttals to previous works. One run of tangentially (at best) related 19th century titles included One Hundred Years Hence, Sixty Years Hence, Two Thousand Years Hence, Fifty Years Hence, Three Hundred Years Hence and Forty Years Hence. The wildly popular 1871 future war epic The Battle of Dorking: Reminiscences of a Volunteer described a Prussian invasion of England and spawned countless works that sought to expand or rebut its premise, including After the Battle of Dorking, The Battle of Dorking: a myth, What Happened After the Battle of Dorking, The Other Side at the Battle of Dorking, Mrs. Brown on the Battle of Dorking, and The Battle of Worthing: why the invaders never got to Dorking.

These works were more utilitarian than artistic and very much concerned with the politics of the moment. Few had literary merit, and even fewer could stand the test of time. But they intrigued readers, whetting appetites for political fiction in general and doom-saying tales of the near future specifically.

The genre’s success also began to attract attention from the literary giants of the day—Edgar Allan Poe was an early dabbler, and a number of Southern writers in his social network soon created more ambitious works, driven in part by the looming threat of American Civil War. That impending crisis drove the emergence of dystopia as a robust narrative fiction genre, with fully fleshed out novels of the near future by professional fiction writers, who appreciated the importance of stories, characters, and above all, action. These works (some of which are discussed here) would cement dystopian fiction as a game-changing political force, thanks to stories that not only reflected the events of the day but helped shape them.

[i] Very loosely translated http://tei.it.ox.ac.uk/tcp/Texts-HTML/free/A68/A68132.html

[ii] Gordon, Walter M. "Thomas More's" Utopia": Preface to Reformation." Renaissance and Reformation/Renaissance et Réforme (1997): 63-79.