Chromatic emancipation

An early Black dystopian author turns his razor-sharp wit on American attitudes toward race

A quick editor’s note: Last week’s newsletter was pretty typo-thick, which happens sometimes when you’re working alone. I’ll try to do better, I promise, and I think this week’s is cleaner, but just in case, I recommend clicking through to the app or web page to get the latest version of the article, rather than reading in email—at least if you’re the kind of person who is bugged by typos. I usually end up correcting a few things each week after posting.

Not long ago in these pages, I told the story of the first dystopian novel by a Black author, or at least the earliest one I’ve been able to find, Imperium in Imperio (1899). Sutton Griggs was only the first in long line of dystopian stories about race from a Black perspective.

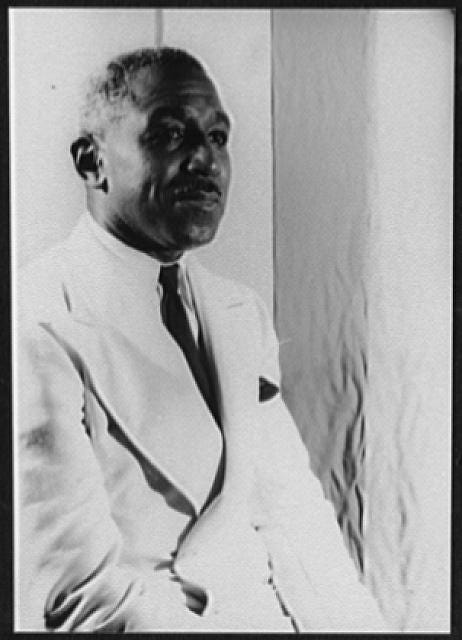

Two of the most clever and creative entries in the genre arrived a few years later. George Schuyler was a journalist writing for the groundbreaking Black newspaper, the Pittsburgh Courier. After dabbling in socialism in his youth, Schuyler slowly became a cynic and a conservative, turning his blistering wit to racial problems in increasingly trenchant terms, often criticizing Black leaders and their “Aframerican” stylings. He married a white Texan woman in 1928, and the next year wrote a pamphlet arguing to solve the “race problem” through interracial procreation, touching on the same third rail that would appall and/or fascinate later White supremacist authors such as Floyd Gibbons and Solomon Cruso.[i]

In 1931, Schuyler’s best-known work of fiction debuted: Black No More: Being an Account of the Strange and Wonderful Workings of Science in the Land of the Free, AD 1933-1940. A particularly memorable entry in the dystopian genre, the book reflected, to some extent, the author’s disenchantment with what he perceived to be the erasure of Black culture through assimilation.[ii] Unlike many dystopian peers of the early 20th century, Black No More has aged well, remaining a modern and engaging read even today. I recommend it to anyone interested in the genre. You can buy it here.

Spoilers begin now.

In the novel, Dr. Junius Crookman, a Black scientist, invents a transformative process that induces an accelerated form of vitiligo—a real medical condition that causes the skin to lose pigment. Readers are most likely to be familiar with vitiligo in relation to pop star Michael Jackson, who claimed the condition was responsible for gradual changes in his skin color that made him appear white.[iii] Crookman intentionally exploits that aspect of the condition, with an extra helping of mad science (“electrical nutrition and glandular control”). As a result of the process, “in three days the Negro becomes to all appearances a Caucasian.” However, the treatment is only skin-deep; the children of those who underwent conversion would still be black.

Founding a company called Black-No-More Inc., Crookman sets out to profit while solving “the most annoying problem in American life. Obviously, he reasoned, if there were no Negroes, there could be no Negro problem.” Crookman “prided himself on being a great lover of his race. … He was so interested in the continued progress of American Negroes that he wanted to remove all obstacles in their path by depriving them of their racial characteristics.”

The company is a wild success, with Black people lining up to pay $50, receive “chromatic emancipation” and start living lives of White privilege. The first man to undergo the process, Matthew Fisher, sets off for Atlanta to woo a White woman who once rejected him for being Black. Seeking a get-rich-quick racket, he joins her father’s White supremacist organization, the Knights of Nordica, and enriches himself and his father-in-law by catering to White fears about “converted Negroes” living among them and diluting their racial purity. While he trenchantly mocks these White racist shenanigans, Schuyler is also biting in his criticism of Black leaders, whom he depicts as conniving to preserve their anti-racism fundraising even as their donors and supporters turn themselves White and abandon the cause.

Operating in the guise of a White man, Fisher builds the Knights of Nordica into a national movement and gets its Grand Wizard nominated for president, but the campaign eventually unravels in a spectacular and somewhat predictable manner. But by the end of the book, there are virtually no Black people left in America, and new prejudices arise against people whose skin is “too light.”

Schuyler continued to write fiction broadly, and dystopian satire specifically, in both published and unpublished works. Starting in 1936, he debuted his second-best-known work, Black Empire, also known as The Black Internationale. Published in serial form by the Courier, the novel was blasted across the front page with the promise of “action… intrigue… thrills… an amazing story of a black genius against the world.”

Schuyler’s views had become “militaristic,” to use his word, as he watched European powers play games with African lives, particularly in Ethiopia and Liberia, the former threatened by Italian imperialism, the latter beset by what Schuyler saw as an exploitative oligarchy. He vented his anger on the pages of the Courier, in editorial columns and in a torrent of race-related fiction, including short and serialized works.

Dr. Henry Belsidus is the black genius of the headline, a radical African-American who leads the Black Internationale, a terrorist group with global reach, whose goal is to seize control of Africa back from European colonizing powers. “My ideal and objective is very frankly to cast down the Caucasians and elevate the colored people in their places,” Belsidus explains, and he deems little out of bounds in the accomplishment of his goals. “Murder? Hah! Haven’t they murdered millions of black people? If we murdered one of them every day, it would take us several centuries to catch up.”

The Internationale keeps extensive surveillance files on potential recruits, seeking to track “every Negro of promise to our cause.” Recruiting the best Black scientists, he commits them to developing economic and military weapons unheard of in the white world, including what we now know as fax machines and solar power, in addition to “electric ray machines” and, most devastatingly, chemical and biological weapons.

The Internationale unleashes a variety of conventional and unconventional attacks, including gassing the titans of British commerce, and devastating Paris and Rome with bubonic plague. The campaign eventually destroys Europe’s economy and liberates Africa, at the cost of millions of white lives. In his blood-soaked moment of triumph, Doctor Belsidus incongruously admonishes his supporters to “banish race hatred from your hearts” and focus instead on the self-improvement of the new Black Empire.[iv]

Writing to a Pittsburgh Courier colleague, Schuyler called the novel “hokum and hack work of the purest vein. I deliberately set out to crowd as much race chauvinism and sheer improbability into it as my fertile imagination could conjure.” But if Schuyler intended the work to be read as absurdist satire, it effectively echoed many elements of the genocidal White supremacist oeuvre that preceded and followed it. Readers took it more seriously than he liked and greeted it more enthusiastically than he anticipated. “The result vindicates my low opinion of the human race,” he wrote.[v]

Except for his youthful flirtation with socialism, Schuyler was no radical, either in his own mind or by any meaningful external definition. His 1966 autobiography was titled Black and Conservative, and he reserved some of his most trenchant criticism for black activists, even going so far as to blame the 1965 Watts riots on Martin Luther King Jr. for “infecting the mentally retarded with the germs of civil disobedience.”[vi]

But he still heard the siren call of racial retribution, which appeared again and again in both his fiction and non-fiction writing—his short stories for the Courier included titles such as “Georgia Terror: Those Who Live by the Sword Shall Die by the Sword,” a tale about a black vigilante group known as the “Merciless Avengers.” Another title, written after Black Empire, described a black insurrection against the Italians in Ethiopia.

Like Sutton E. Griggs before him, Schuyler navigated a difficult and conflicted course between competing impulses toward separatist militancy and cooperative coexistence. Some 30 years later, their literary successors would usher in a new wave of black revolution without apology or accommodation.

To be continued…

[i] http://www.mixedracestudies.org/?tag=george-s-schuyler

[ii] Schuyler, George S. "The Negro-art hokum." African American Literary Theory: A Reader (1926): 24-26. http://www.blackpast.org/aah/schuyler-george-1895-1977

[iii] https://www.umassmed.edu/vitiligo/blog/blog-posts1/2016/01/did-michael-jackson-have-vitiligo/

[iv] http://www.brothersjudd.com/index.cfm/fuseaction/reviews.detail/book_id/16/Black%20Empire.htm

[v] Black Empire https://archive.org/details/blackempire00schu/page/260

[vi] Lock, Helen. "George S. Schuyler, Black and Conservative." ethn stud rev 32.2 (2009): 79-91.